COP28: What to expect from the first Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement?

[April 2023] COP28 (hosted by the United Arab Emirates) will mark eight years since the Paris Agreement was signed. State Parties will review and assess the "collective progress" made towards the achievement of the agreement and its long-term goals, in the first ever Global Stocktake. What to expect from this meeting?

Analysis note by the Global Observatory of Climate Action

- Author: Antoine Gillod, Director of the Global Observatory of Climate Action

- Date: April 2023

- Contents

- One objective: To evaluate « collective progress »

- A two-year process to build a common vision

- Expected results

- The role of non-state actors

- The Observatory’s Lens: Shifting from the era of engagement to that of impact

-

ONE OBJECTIVE: TO EVALUATE “COLLECTIVE PROGRESS”

The objectives of the Global Stocktake were defined in Article 14 of the Paris Agreement: the COP shall « periodically take stock of the implementation of this Agreement to assess the collective progress towards achieving the purpose of this Agreement and its long-term goals (global stocktake)”.

The term « collective progress » is central: this is not a « name-and-shame » exercise, ranking or scoring individual states on the basis of progress. The decisions taken in Katowice at COP24 are even more explicit in this regard: the Global Stocktake « should not be targeted at any particular Party and should include a non-prescriptive review of collective progress« .

This approach is consistent with the spirit of the COP21 negotiations, which made it possible for all 193 UNFCCC States to join the Paris Agreement. Rather than a « top-down » approach that sets a universal target and allocates specific goals (as in the Kyoto Protocol), the Paris Agreement has established a « bottom-up » pledge-and-review system: each Party freely sets its level of ambition, and the collective framework is responsible for encouraging each to implement its commitments and raise its ambition regularly.

Article 14.3 is very clear in this regard: the results of the Global Stocktake are intended to “[inform] the Parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, their actions and support.”

No form of sanction is therefore to be expected against States that have not respected their commitments: compliance is not the issue here. No prescriptive recommendation should be made at the end of COP28 either. UN diplomacy seeks above all to find the lowest common denominator for all States in order to encourage action: it is therefore the Parties that will be responsible for the conclusions to be drawn from this global assessment.

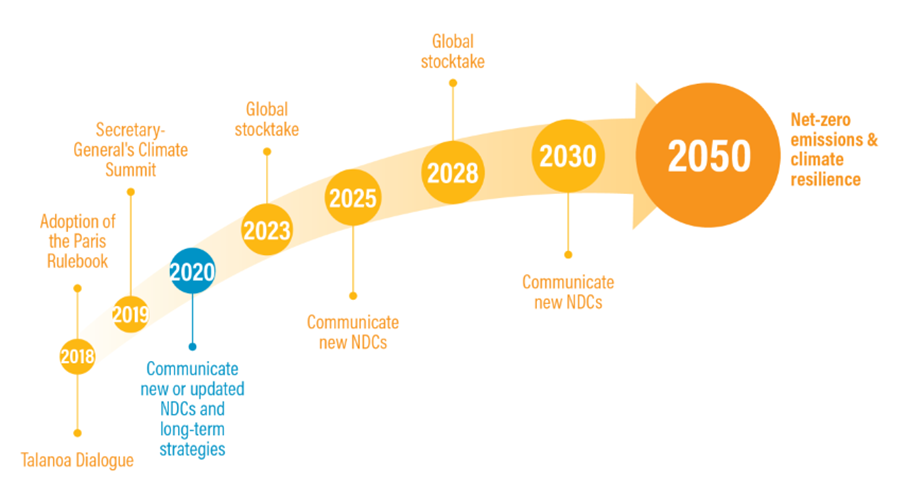

Thus, this first Global Stocktake is a pivotal moment in the ambition cycle. It is part of a precise and regular calendar set up by the Paris Agreement to organize the renewal and strengthening of the ambition of nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Scheduled to take place every five years starting in 2023, the Global Stocktake takes place within a cycle of communications and renewals of ambition (Figure 1). It complements the « enhanced transparency framework » under Article 13 of the Paris Agreement, which requires States to disclose in their biannual reports a certain amount of information necessary to track implemented measures and progress on climate change mitigation, adaptation actions, and support provided or received.

The conclusions of this first Global Stocktake will probably be unsurprising: States’ commitments are not up to the goals of the Paris Agreement, as already assessed by the UNEP, and Parties will be encouraged to strengthen their ambition and increase the scale of their action.

A TWO-YEAR PROCESS TO BUILD A COMMON VISION

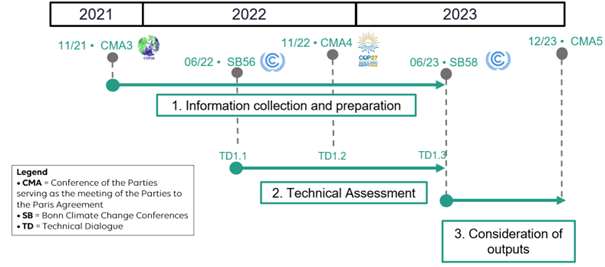

Prior to the final meeting at COP28, the Global Stocktake followed a two-year process, organized into three « components » or « phases » (Figure 2). The rules and principles of this process were set out in the Paris Agreement rulebook, which was largely adopted at COP24 in Katowice (decision 19/CMA.1):

- Information collection and preparation

- Timeframe: From the COP26 to the Bonn Conference in June 2023

- Objectives: To collect, compile and synthesize the information necessary to prepare the technical evaluation phase.

- Sources of information: Reports from the UNFCCC secretariat, IPCC reports, voluntary submissions from Parties, but also submissions from « Observer » actors such as NGOs, companies, community networks, etc.

- Technical assessment

- Timeframe: From the Bonn Conference in June 2022 to the Bonn Conference in June 2023

- Objectives: To « assess collective progress toward achieving the purpose and long-term goals of the Agreement« . Three technical dialogues are being held between 2022 and 2023 to create spaces for discussion among the Parties and Observers.

- Expected results: Synthesis reports

- Consideration of outputs

- Timeframe: From the Bonn conference in June 2023 to the COP28 in December 2023.

- Objectives: To consider the implications of the findings of the technical assessment in order to inform Parties on progress and encourage them to increase their ambition through their NDCs and international cooperation. This ambition is not limited to emission reductions, but also includes adaptation, means of implementation and equity.

- Expected results: A decision and/or political declaration signed by the Parties

The Global Stocktake will facilitate the assessment of Parties’ progress on three pillars of the fight against climate change:

- Mitigation

- Adaptation

- The means of implementation and support, in the light of equity (this includes financial issues and just transition).

The work will pay particular attention to enabling actions that address the economic and social consequences of climate change (« response measures« ), as well as addressing the adverse effects of climate change on human and natural systems (« loss and damage« ).

At COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, the Subsidiary Bodies planned new consultations with Parties and non-Parties on the « results » component. Two meetings organized in April and October will mark the year to mobilize stakeholders around the Global Stocktake.

EXPECTED RESULTS

Little is known yet about the final form of the Global Stocktake results as they will be presented at COP28. Decisions voted on by the Parties at the COP28 will be adopted, and a political declaration may also emerge from this process. The Katowice decisions state that Parties are invited « to present their nationally determined contributions, informed by the outcome of the Global Stocktake, at a special event held under the auspices of the Secretary-General of the United Nations”

In the meantime, a Climate Ambition Summit will be held in September 2023, organized at the initiative of Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, to push for more tangible and credible action on the part of the largest emitting countries.

WHAT ABOUT NON-STATE ACTORS?

The Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) are encouraging non-Parties to organize events to feed into the Global Stocktake. For example, ICLEI, an international network of cities committed to sustainable development, is encouraging its members to take advantage of the opportunity to organize « local stocktakes » of climate action implementation.

But, beyond the contributions of non-state actors to the UN process —that is centered on States— there is an emerging concern to assess the progress of committed businesses, local governments and civil society organizations. Indeed, since the IPCC’s 1.5 °C report in 2018, the « net zero wave » has committed many companies, cities, regions and public or private institutions to a decarbonization trajectory consistent with the goal of limiting global warming to below 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial level. The Race to Zero campaign currently lists more than 11,300 actors around the world, including 8,307 companies, that have set a carbon neutrality goal.

In response to this momentum, in March 2022 Antonio Guterres convened a High-Level Expert Group on Net Zero Emissions Commitments by Non-State Entities, which delivered its report at COP27 with recommendations to promote greater integrity in corporate net zero commitments. In Europe (CSR directive on corporate social responsibility) and in the United States (Securities and Exchange Commission project), new mandatory rules are being debated to strengthen ESG reporting standards for companies. These regulatory standards are discussed in parallel with voluntary standards, developed by the International Sustainability Standards Board (IFRS standards) and the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GRI standards). We will soon write an article on this subject on the Observatory’s Blog.

The Climate Data Steering Committee (CDSC), launched in June 2022 at the initiative of Emmanuel Macron and Michael Bloomberg, made recommendations during COP27 for the creation of Net Zero Data Public Utility (NZDPU), a centralized repository for data related to the climate transition. Publications such as Global Climate Action 2022 or State of Climate Action 2022 attempt to assess the progress of non-state actors in terms of their ambition or future transition scenarios. Databases such as the System Change Lab or Climate TRACE aim to map indicators on actors’ emissions or industrial transition paths.

THE OBSERVATORY’S LENS: SHIFTING FROM THE ERA OF ENGAGEMENT TO THAT OF IMPACT

To limit global warming to below the 1.5 °C threshold, it is necessary to have an annual drop in emissions equivalent to the one caused in 2020 by the Covid-19 pandemic until 2030, according to the Global Carbon Budget. Yet global emissions are at an all-time high, as they were in 2022. The conclusions of the latest IPCC synthesis report, and the stir caused by the appointment of the CEO of the UAE’s national oil company as President of COP28, indicate the need for a paradigm shift in the mobilization of actors.

Too often, commitments from non-state actors — when they exist — fall short of expected decarbonization trajectories, and lack credible and operational transition plans. Of the 18,600 companies that disclosed their data in the climate category to the CDP, only 0.4% presented a plan considered to be aligned with a 1.5 °C trajectory with demanding targets.

Climate Chance and the World Benchmarking Alliance expressed a common position in the February 2023 Consideration of Outputs consultation to encourage the inclusion of non-state actors in the evolution from engagement and transparency to performance. It is summarized in five points:

- Parties should improve reporting and monitoring of climate action by non-state actors in the context of the Global Stocktake

- Parties must move from a logic of engagement with non-state actors to one of joint responsibility/accountability

- Parties should strive to align the actions and transition plans of non-state actors with sectoral and national decarbonization strategies

- Parties must create an enabling policy and regulatory environment to promote the alignment of non-state actor activities with the Paris Agreement

- Equity, just transition and nature should be at the heart of the Global Stocktake with guidance to support implementation by non-state actors

This last point is also defended, in their own separate contribution to the consultation, by several major groups of non-state actors representing environmental associations (ENGO), youth associations (YOUNGO), women’s associations (WGC) and trade unions (TUNGO) within the UNFCCC. They advocate that the Parties should take an interest in the impact of climate policies and actions on the population, from a perspective of just transition and the protection of human rights.

Therefore, we believe it is necessary to initiate, on the occasion of this first Global Stocktake, an evaluation of the existing reporting and public policy assessment frameworks, in order to encourage Parties to increase their accountability and that of non-state actors with regard to their transition plans and their real impacts on the climate in a spirit of social justice.