Non-Financial Reporting Standards: What Impact on Corporate Climate Accountability?

[June 2023] Several new regulatory and private standards are being developed to address ESG reporting practices. Just before the Global Stocktake that will assess the collective progress of the Parties of the Paris Agreement, the Observatory of Climate Action questions the expected impact of these new norms.

Analysis note by the Global Observatory of Climate Action

- Author: Antoine Gillod, Director of the Global Observatory of Climate Action

- Date: June 2023

- Contents

- International stage: the ISSB’s work

- In Europe: the CSRD strengthens and broadens obligations

- In the United States: the SEC, a project on hold

- Materiality: what are companies accountable for?

- The Observatory’s Lens: beyond reporting, accountability

Launched in 2021 at COP26, the Race to Zero campaign lists 8,307 companies worldwide that have set a carbon neutrality target. In this context of massive adoption of the language of « neutrality », the credibility of the commitments depends on the ability of actors to rely on robust standards to 1) take stock of their emissions, 2) set targets, 3) formulate transition plans, 4) implement actions and 5) assess their impact on emissions.

For each of these stages, numerous public and private initiatives have been and are still being developed to assess the transparency, credibility and impact of commitments. The same applies to the accountability of the actors involved.

In 2023, three major projects to standardize non-financial reporting standards will frame, regulate and attempt to harmonize corporate sustainability disclosures:

- The International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB), launched by the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation at COP26;

- The European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), as part of EU Directive 2022/2464, known as the « CSRD » (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive);

- The Rule on Climate-Related Disclosure proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in April 2022.

Each of these standards will establish or update rules for the disclosure of information relating to impacts and/or risks on the environment, society, and the company’s economic ecosystem. This article summarises the ambitions and progress of each of these projects, and follows with an analysis of the points of contention and concerns raised by all of them.

International stage: the ISSB’s work

On November 04, 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, the IFRS Foundation announced the creation of the International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB), an initiative aimed at developing an international standard for non-financial reporting. This private initiative is aimed at financial actors, to provide investors with information on the risks and opportunities associated with corporate sustainability.

The creation of the ISSB is in response to requests from the G20, which already initiated the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) in 2015, and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) – an association of national financial authorities (e.g. the Securities and Exchange Commission in the USA, the Autorité des Marchés Financiers in France, etc.) – to harmonise non-financial reporting frameworks.

The ISSB’s work should result in two standards that will be in effect by January 2024:

- IFRS S1 on General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information

- IFRS S2 on Climate-related Disclosures

The new IFRS standards will be aligned with the TCFD guidelines, as well as with the guidelines of two entities that were « consolidated » within the IFRS during 2022: the Value Reporting Foundation, which promotes the integration of financial and non-financial reporting, and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), an initiative launched in 2007 by the CDP. These two organisations are now an integral part of the ISSB, contributing to the trend towards convergence of reporting methodologies and standards that has been underway for several years (see Global Synthesis Report on Climate Finance 2022). Alignment with the TCFD’s recommendations clearly places IFRS within the scope of a simple materiality.

The scope of application of ISSB standards will depend on their adoption by national financial authorities which may wish to use them as a basis for regulation. This is the case, for example, in Australia and the Hong Kong stock market.

With regard to IFRS S2 on climate, the ISSB requires the publication of a transition plan, a resilience analysis, a set of metrics (Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, low-carbon capital expenditure, etc.) and quantified targets.

In Europe: the CSRD strengthens and broadens obligations

Since 2014, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) has required companies with more than 500 employees to disclose a certain amount of information relating to their extra-financial performance in their annual reports.

As part of the European Green Deal, the European Commission has undertaken the revision of the NFRD, in order to strengthen a harmonised reporting framework for corporate ESG data. The new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), voted on in the autumn, came into force on January 5th, 2023.

This is the 3rd pillar of the European Union’s Green Finance Strategy under the European Green Deal, along with the SFDR on extra-financial reporting by investors, and the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities (see Global Synthesis Report on Climate Finance 2022).

What impact will this directive have?

- Firstly, the CSRD will significantly extend the scope of the reporting obligation from 11,000 to 50,000 companies; many companies with more than 250 employees will now be subject to it, including listed SMEs.

- Secondly, the CSRD is intended to increase the degree of detail in the information required from companies. EFRAG is responsible for developing the content of the reporting standards. Built in line with the EU Taxonomy, the information disclosed will make it possible to assess a company’s « sustainability » in terms of harmonised, demanding criteria.

- Finally, the CSRD introduces the concept of double materiality (see below).

EFRAG was therefore tasked by the European Commission with preparing new sustainability reporting standards. At the end of November 2022, EFRAG presented twelve standards to the Commission, incorporating the opinions expressed during a public consultation between April and August 2022. These twelve standards are organised into four categories addressing the different ESG issues encountered by a company:

- Cross-cutting issues (2 standards)

- Environmental issues (5 standards)

- Social issues (4 standards)

- Governance issues (1 standard)

EFRAG’s proposed standard on climate change (ESRS E1) is set out in a 53-page document that specifies all the information and metrics required to assess the impact, risks and opportunities associated with climate change.

However, from Spring 2023, various sources indicate that the European Commission plans to waive certain mandatory indicators, including disclosure of Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions (Responsible Investor, 17/05/2023).

In the United States: the SEC, a project on hold

In March 2022, the commissioners of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the US federal agency that regulates and oversees financial markets, voted in favour of a proposal that would require public companies to publish their greenhouse gas emissions (Scope 1 and 2), and have them audited and verified by a third party. US and foreign companies registered with the SEC would also have to publish an annual emissions reduction plan. Contrary to the work of the ISSB and EFRAG, this proposal does not extend to all ESG criteria, and focuses only on climate-related financial information.

Adoption of the SEC’s proposed new rules has been delayed. A computer glitch has prevented the registration and consideration of many the numerous public comments made since the proposal was announced in March; on the other hand, a June 2022 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency holds that state agencies (such as the EPA or SEC) must obtain Congressional approval to create regulations with major economic and political effects.

The proposal also contends with conservative political opposition. Even before the proposal was published, the Attorney General of the State of West Virginia declared that he was ready to sue the SEC, on the grounds that the obligation to publish its emissions, particularly in Scope 3, violates the First Amendment of the Constitution. In early May 2023, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law a bill aimed at preventing public officials from investigating the environmental, social and governance impacts of public spending. The law also prohibits the sale of ESG bonds. Many companies also oppose the bill.

This proposal echoes the plan announced by Joe Biden at COP27, requiring companies that receive more than $50m a year in public contracts to disclose their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, relevant Scope 3 information, climate-related financial risks and science-based emission reduction targets.

Materiality: what are companies accountable for?

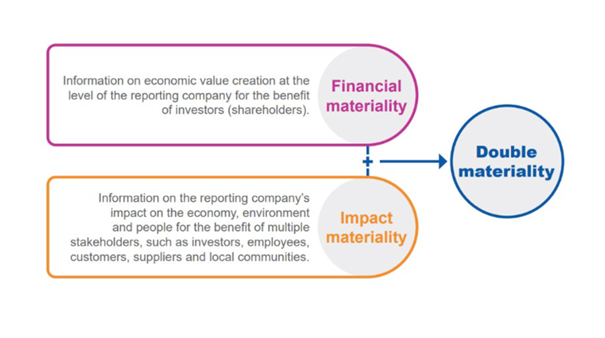

In accounting terminology, the term « materiality » is used to designate the relevant information to be taken into account in a company’s reporting. In terms of ESG, there are two types of materiality, well described in this note from the Global Reporting Initiative (figure):

- Financial materiality, which consists in assessing the risks and opportunities of the environment/climate change for the company’s financial performance (this is known as climate-related financial disclosure, for example).

- Impact materiality, which consists in accessing the company’s impact on its economic, environmental and social environment for all stakeholders.

Why is this important? Depending on the materiality chosen, reporting will serve two different purposes: the stability of financial markets on the one hand (financial materiality), and corporate accountability on the other (impact materiality). We speak of « double materiality » when reporting frameworks take both approaches into account.

In the ISSB framework, this is a « simple materiality », purely financial. Based on the TCFD, VRF and CDSB guidelines, the new IFRS standards have no other ambition than to improve the anticipation and management of ESG-related financial risks and opportunities. An example of a concrete consequence: companies will be required to disclose how their objectives are « informed by » international agreements such as the Paris Agreement and national or subnational objectives – but not to » compare to » these objectives.

The standards prepared by the SEC follow the same logic and focus on climate-related financial information. According to SEC Chairman Garry Gensler, these standards will “provide investors with consistent, comparable, and decision-useful information for making their investment decisions”.

For their part, the ESRS standards prepared by EFRAG will follow the « double materiality »[1] principle laid down by the CSRD and NFRD. They will therefore organise the reporting of information relating both to the development of the company’s business and its situation, and to the impact of its activities on ESG issues.

The Observatory’s Lens: beyond reporting, accountability

The Observatory welcomes any initiative to standardize and harmonize reporting practices for data useful in understanding, monitoring and evaluating corporate climate action. Data is vital to our work, and data quality and uniformity are essential to any exercise involving large-scale comparison and aggregation of the progress observed.

Nevertheless, data disclosure is a necessary but insufficient condition for assessing the real contribution of non-state actors to international climate objectives. Eight years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, extra-financial reporting, however precise it may be, is not enough to provide a reliable measure of actors’ commitment, let alone their results. Apart from the European framework, these transparency standards have no other purpose than to fill an information asymmetry between a company and an investor, in order to ensure the stability of the financial system. They say little or nothing about the credibility of transition plans and the results achieved by the actors involved.

In particular, simple materiality reporting frameworks share a common understanding of the risks and opportunities that climate change represents for companies’ financial performance. What the TCFD recommendations, IFRS standards and SEC rules have in common is that they were initiated by financial authorities (the FSB, IOSCO and SEC respectively), while European standards are primarily the result of legislative work by the EU’s political institutions. Aside from the European framework, these standards have no other purpose than to overcome an asymmetry of information between a company and an investor, in order to ensure the stability of the financial system.

This objective is not insignificant, but neither is it neutral in terms of climate accountability. Ultimately, all these initiatives are linked by a shared trust in « market regulation » and in the ability of actors to make rational, self-determined decisions on the basis of available information[2]. A faith shared by all the political forces involved. It is symptomatic, for example, that the Biden-Harris plan announced at COP27 does not link the obligation for companies to submit a carbon footprint when they enter into contracts with the federal government with an obligation to achieve results, or even to demonstrate the credibility of their decarbonization strategy, in order to gain access to public contracts.

Those concerned with corporate climate accountability cannot therefore fully rely on extra-financial data designed for financial actors to assess the impact and progress made towards achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement. In the run-up to the Global Stocktake, which will observe the collective progress made by the Parties to the Paris Agreement at COP28, it is urgent that non-state actors, international institutions and the stakeholders align themselves with the best standards of climate accountability.

Notes:

[1]The 2014 and 2022 European directives use the term « double materiality perspective », which means the same thing.

[2] Bretts, C. (2017). Climate Change and Financial Instability: Risk Disclosure and the Problematics of Neoliberal Governance. Annal of the American Association of Geographers, vol. 107 (5), pp. 1108-1127

References

Adams, C. (09/03/2021). EU v IFRS: Fundamentally different approaches to sustainability reporting. drcaroladams.net

Baddache, F. (22/11/2022). « Reporting ESG : Comprendre les 12 normes proposées par l’EFRAG». ksapa.org

Bretts, C. (2017). Climate Change and Financial Instability: Risk Disclosure and the Problematics of Neoliberal Governance. Annal of the American Association of Geographers, vol. 107 (5), pp. 1108-1127

EFRAG (15/11/2022). Draft as of 15 November 2022 prepared solely for approval by the EFRAG SRB and still subject to editorial review before it is finally issued. efrag.org

Global Reporting Initiative (22/02/2022). The materiality madness: why definitions matter. The GRI Perspective, issue 3. globalreporting.org

Holmstedt Pel, E. (17/05/2023). EC considers ditching mandatory indicators in first set of EU sustainability reporting rules. Responsible Investor

IFRS (03/11/2021). IFRS Foundation announces International Sustainability Standards Board, consolidation with CDSB and VRF, and publication of prototype disclosure requirements. Ifrs.org

Kenway, N. (14/12/2022). Australia sets sights on mandatory climate disclosure. ESG Clarity

Mufson, S. (02/05/2023). Biden’s push to disclose climate risks hits wall of industry resistance. The Washington Post

PRI (Mars 2023). ISSB Decisions on the First Set of IFRS Sustainability. Principles for Responsible Investment

Ramonas, A., Iacone, A. (19/10/2022). SEC Climate Rules Pushed Back Amid Bureaucratic, Legal Woes. Bloomberg Law

Segal, M. (17/04/2023). Hong Kong Exchange to Require Climate Reporting from All Issuers Beginning 2024. ESG Today

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (n.d.). Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures. Sec.gov

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (21/03/2022). SEC Proposes Rules to Enhance and Standardize Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors. Sec.gov

Vanderford, R. (25/04/2023). SEC’s Climate-Disclosure Rule Isn’t Here, but It May as Well Be, Many Businesses Say. The Wall Street Journal

White House (10/11/2022). FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Proposes Plan to Protect Federal Supply Chain from Climate-Related Risks. Whitehouse.gov

Williams, C. A., Eccles, R. G. (23/11/2022). Review of Comments on SEC Climate Rulemaking. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

Wyatt, K. (18/08/2022). US and European Climate Reporting: Is the Distinction Between Single and Double Materiality Overblown? Persefoni